Using Research to Problematise ‘The Good Practicum’

“Traditional” Teachers: Current Teaching Methods and Nurturing Independent Learners

April 7, 2019

Mentor education matters

April 22, 2019

Most student teachers have positive experiences of working in a school when on placement. A minority, however, return to university from their placement feeling stressed and anxious. In Scotland, The Donaldson Review (2011) claims that 23% of their respondents admitted to having ‘variable or very poor’ placement experiences. Problematic experiences have been reported in a range of empirical studies throughout the wider world (see for example Boz and Boz, 2006), so the issue is a familiar one across national systems of teacher education.

Cathy and Tom - divergent experiences

During a recent research project, I came across two students with divergent experiences. Referring to colleagues in the department, one said, ‘I don’t think they could have done any more to help and support me’ (Cathy (pseudonym)); the other remarked, ‘I don’t understand why they had to make my time in the school so difficult’ (Tom (pseudonym)). Interestingly, they were both placed in the same subject department and had worked with the same colleagues! Given this commonality, how could these students have had such contrasting experiences?

"Good placements" or "poor placements"

In exploring the nature of placement experiences, it is tempting to make reference to ‘good placements’ or ‘poor placements’, seeking to attribute responsibility for the quality of the student’s experience to the school or department. Such a view, however, would find it hard to explain why the student teachers in the research had such different experiences in the same context.

Researching the experiences of the two student teachers, I discovered that individuals make more significant contributions to their own learning and development than might have been previously assumed if a more socially deterministic view had been taken. Data from the project suggest that the students were actively responsible for shaping and influencing the kinds of support available to them on placement. What seemed to make a difference to their manner of engagement was their prior experiences of learning and work. This is not to say that they were able to act unfettered from social influences: they did not have complete licence to act in ways that marked them as free from social constraints.

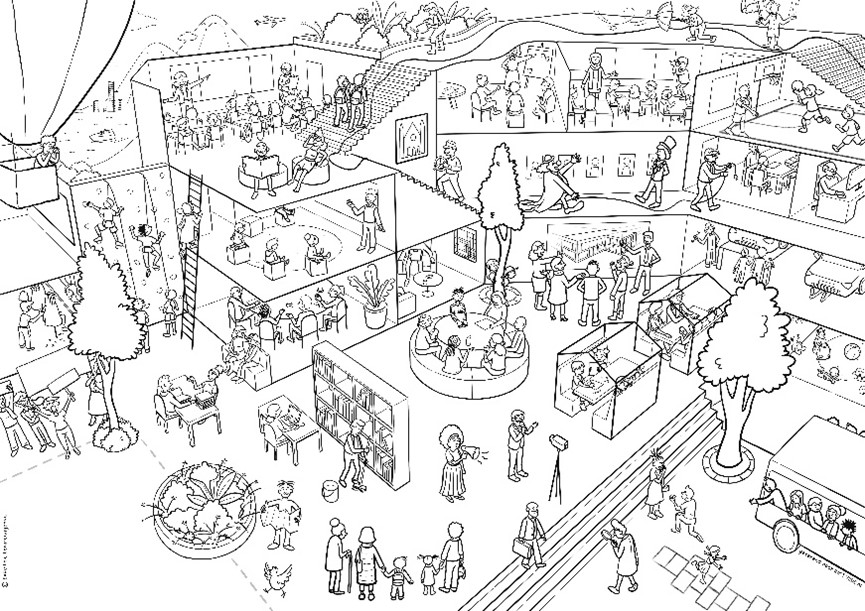

The research examines why two student teachers get on very differently while on placement in the same department.

The research examines why two student teachers get on very differently while on placement in the same department.

Their contributions could best be viewed as taking place in relation to the nature of the circumstances they were an important part of. Therefore, it is important to explore the way individuals and their (placement) contexts become mutually constituted and constitutive (Flores and Day, 2006). They are relationally interdependent in the sense that what takes place on placement emerges as a product of the way individuals take up the opportunities for learning and development afforded by the context (Billett, 2009).

Cathy - in the middle of everything

Cathy belonged to a family of teachers’ always enjoying the feeling that she was ‘in the middle of everything’ and at school she tried to get involved in as many activities as possible. A self-confessed ‘people person’, she worked abroad for four years as an English language teacher, eventually being promoted. She viewed herself as a ‘chameleon’, being able to adapt to whatever circumstances present themselves to her.

Starting her placement, she immediately looks for opportunities to become involved in her department, getting to know her colleagues by spending time talking with them. She makes connections to teachers outwith the department, leading to invitations to a range of whole school activities. She adapts her working schedule around her department’s request to have lesson plans submitted in advance of lessons, and so teachers come to see her as hard-working and committed. Her positive relationships give her the confidence to ask questions or seek help if required. The positive rapport she develops with colleagues goes beyond the professional, spilling out into the personal domain.

Tom - a solitary learner

Tom, on the other hand, views himself as a ‘solitary learner’ who enjoyed working autonomously when a school pupil himself. Whilst undertaking his undergraduate degree, his part-time work as a bingo caller involved him in managing a team of mainly part-time workers. He felt that his contributions were valued there and that he was important to the success of the operation - vital to his motivation as a worker. He preferred interacting with people for whom he felt a personal connection and relished in particular the culture of work where there was a strong emphasis on informal socialising with other colleagues after work finished.

In the placement school, he is reserved in his interactions with colleagues, preferring to find quiet opportunities where he can get on with planning independently. He tries to work things out himself and does not want to bother his colleagues as he sees they are busy. Teachers thus do not get to know Tom so well. Additionally, his plans aren’t shared in advance, and so they begin to question his commitment. The nature of his interactions with colleagues becomes more strained as time goes on. Although making close links to two teachers whom he likes personally, he is unable to build a sense of connection to the team, or to feel valued, or that what he is doing is considered important. He is uncomfortable in the more formal school culture.

The notion of a ‘good practicum’

From these brief descriptions it can be seen that the student teachers’ prior experiences and dispositions play out very differently as they begin their placement, leading to very different responses from teaching colleagues and, in the longer term, different experiences of working in the same department. The notion of a ‘good practicum’ is thus problematized as this way of conceptualising school experience promotes the contribution of the placement as something that exists separate from the activities of the student teachers who participate in it. However, student teachers contribute in significant ways to the circumstances around their support (Hayes, 2001) and this raises implications for the way they are able to engage with the possibilities for learning and development in the placement school.

References

Billett, S., (2009). Relational Interdependence Between Social and Individual Agency in Work and Working Life. Mind, Culture and Activity, 13(1), pp53-69.

Boz, N., and Boz, Y., (2006). Do prospective teachers get enough experience in school placements? Journal of Education for Teaching, 32(4), pp353-368.

Donaldson, G., (2011). Teaching Scotland’s Future: Report of a Review of Teacher Education in Scotland. Edinburgh; Scottish Government.

Flores, M., A., and Day, C., (2006). Contexts which shape and re-shape new teachers’ identities: a multi-perspective study.Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, pp 219-232

Hayes, D., (2001). The Impact of Mentoring and Tutoring on Student Primary Teachers’ Achievements: a case study. Mentoring and Tutoring, 9,(1), pp.5-21.