21st century creative pedagogy: its importance in teacher education

Pre-service teachers as agents of change in the new Computing curriculum

August 11, 2017

Secondary (11-19) and specialist teacher identity in England

August 24, 201721st century creative pedagogy: its importance in teacher education

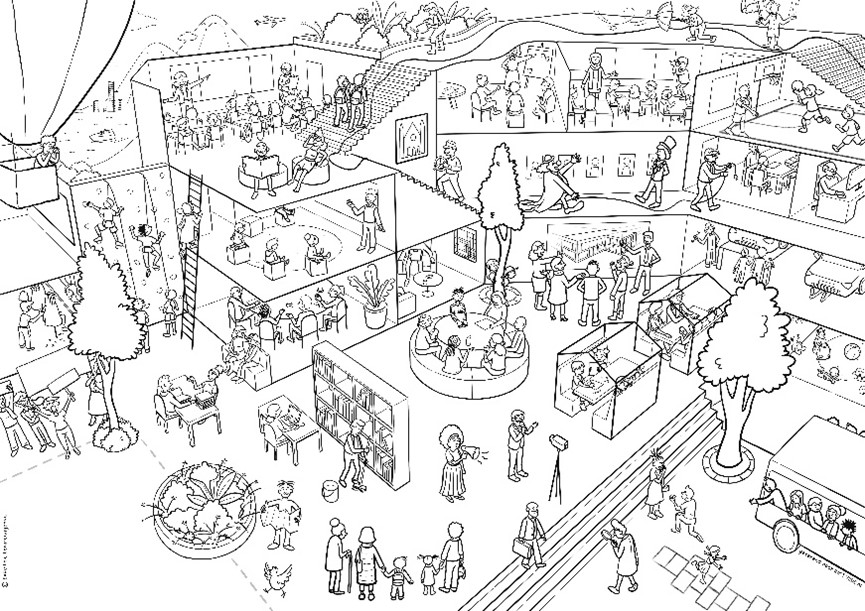

21st century English school-based education and learning debatably needs rethinking. Our classrooms repeatedly still mirror those of the Victorian era and education may be viewed as ‘traditional’ and ‘boring’ with pupil motivation and engagement frequently a problem (Hamari, 2015; Lynch, 2016). Lessons are often not reflective of a rapidly developing 21st century landscape. Performativity, accountability and compliance founded upon drilled learning and continuous testing as the measure of successful pupil progression is arguably the dominant discourse for an ‘effective’ teacher (Sharrit, 2008). However, this does not educate and prepare our children for the 21st century they occupy (Hicks, 2006). To be successful contributors to a 21st century society and economy, children should be encouraged to take risks with their learning, challenge conventional boundaries, critically engage with the world around them, solve problems, develop resilience, be innovative and imaginative, make mistakes and have the freedom to express themselves. Exposure to creative scholarly pedagogy that inspire these learning facets is vital. ‘Teaching to the test’, simply establishing who has ‘done’ what in class and regurgitating knowledge and facts in public examinations may increase our standing in world education league tables but it will not be sufficient in developing the skillset and expertise our young people now need to engage with their 21st century futures (Aslan, 2015; Cozar-Gutierrez & Saez-Lopez, 2016).

We need to develop teachers who have the critical expertise to appreciate the need for progress measures and outcome accountability, but not at the expense of creative, ‘outside of the box’ learning approaches

We need to develop teachers who have the critical expertise to appreciate the need for progress measures and outcome accountability, but not at the expense of creative, ‘outside of the box’ learning approaches

As teacher educators, we need to model creative pedagogy with our pre-service colleagues. We need to develop teachers who have the critical expertise to appreciate the need for progress measures and outcome accountability, but not at the expense of creative, ‘outside of the box’ learning approaches. We need to encourage our trainee teachers to foster the skills required to become transformational agents of change in their future classrooms and schools. We need to develop recognition that a 21st century ‘classroom’ no longer needs to mimic its Victorian ancestry and that out pupils may demand their learning is contextualised and approached through alternative pedagogies.

With this in mind, pre-service teachers could be encouraged to use gamification as a pedagogic means to creatively engage their pupils. Gamification is the use of game elements in non-game contexts (Deterding et al, 2011). Gamification aims to inspire and motivate by incorporating typical video game dynamics, mechanics and aesthetics to develop learning, progress and problem solving proficiency (Kapp, 2012). Gamification enables pupils to learn using video game design and game-based learning without the need to use a video game itself (Kingsley & Grabner-Hagen, 2015). This can be achieved by enabling the use of rewards, badges, competition, leaderboards, levels, mystery, characterisation, narrative, exploration, curiosity, surprise, challenge and excitement. Gamification enables teachers to contextualise the learning using pedagogy that their pupils will find accessible and engaging in the 21st century. After all, 99% of 8 to 15 year olds in the United Kingdom play digital video games (IAB, 2014). Through playing these games (or indeed utilising elements of these games), children are learning (Gee, 2003). They are developing resilience. They are problem solving. They are making mistakes. They are being imaginative. They have the freedom to express themselves and create. They are collaborating. They are challenged. They are immersed in the surprise, mystery and fantasy that is motivating and captivating them to play and to continue to play. They are succeeding. They are developing fundamental 21st century skillsets.

Testing and summative progress measures are important in an education system and teacher education programmes. However, the concluding message form this post is that teacher education needs to be developing creativity, risk taking and criticality in our pre-service teachers that enables our pupils’ thinking to be challenged. Our teacher education courses also need to be reflective of learning contexts and pedagogical approaches that will enhance creativity and engagement in the classroom and therefore support the expertise that our young people require to successfully connect with their 21st century futures.

References

Aslan, S. (2015). ‘Is Learning by Teaching Effective in Gaining 21st Century Skills? The Views of Pre-Service Science Teachers’. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice. 15(6). 1441-1457.

Cozar-Gutierrez, R., and Saez-Lopez, J.M. (2016). ‘Game-based learning and gamification in initial teacher training in social sciences: an experiment with MinecraftEdu’. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 13(2). 1-11.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). ‘From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining gamification’. Proceedings of the 15th international Academic Mindtrek Conference (pgs 9-15). ACM.

Gee, J.P. (2003). ‘What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy’. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Hamari, J. (2015). ‘Challenging games help students learn’. Gamification Research Network.

Hicks, D. (2006). ‘Lessons for the Future: The Missing Dimension in Education’. Victoria BC: Trafford Publishing.

Internet Advertising Bureau. (2014). ‘Gaming Revolution’.

Kapp, K. (2012). ‘The gamification of learning and instruction: game-based methods and strategies for training and education’. Wiley.

Kingsley, T., & Grabner-Hagen, M. (2015). ‘Questing to Integrate Content Knowledge, Literacy and 21st Century Learning’. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 59(1). 51-61.

Lynch, M. (2016). ‘Gamification Can Reinvigorate Teaching and Learning: An Introduction’

Sharritt, M. (2008). ‘Forms of Learning in Collaborative Video Game Play’. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning. 3(2). 97-138.