Boundaries and boundary-crossing

Yvonne Bain, Jurriën Dengerink, Donald Gray

[tabby title=”Introduction”]

Setting the scene

In thinking about who are the teacher educators, we consider teacher educators in Higher Education, teacher educators in the school settings supporting beginning and new teachers, as well as those who span both contexts as part of their professional role. This theme seeks to explore a few key questions in relation to the boundaries that exist and the impact of engaging in practice at or across boundaries.

- In what ways do boundaries enable or constrain the development and the practice of teacher educators?

- How do teacher educators navigate the transitions between boundaries?

- What is the impact of learning at the boundaries in relation to the development of teacher educators?

The literature review by Akkerman and Bakker (2011) highlights that boundaries, boundary crossing and boundary objects arise from a number of contexts and studies in a range of professional settings. Considering their definition of boundaries as “sociocultural differences that give rise to discontinuities in interaction and action” (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011:133) the different boundaries for different professional settings and contexts create opportunities for professional and personal transitions. This theme offers an opportunity to explore how the boundaries influence, shape or transform ourselves and / or our practice as teacher educators.

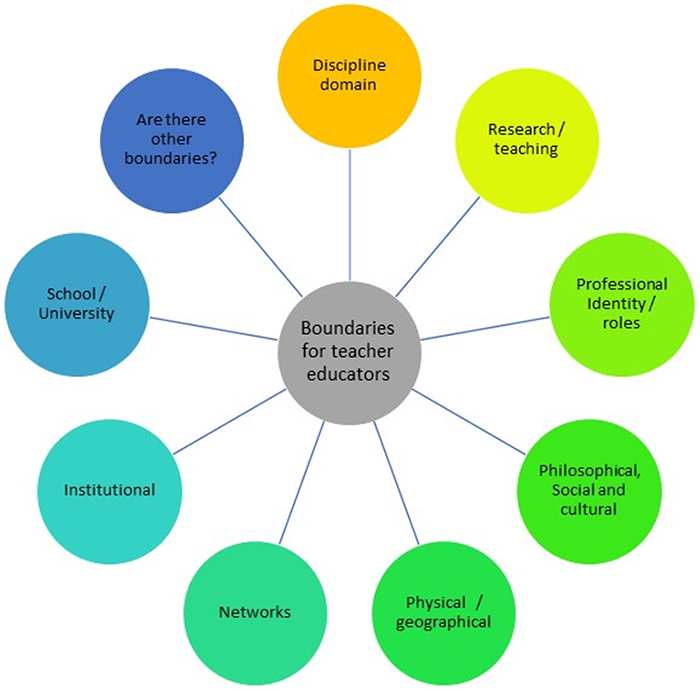

The mind-map diagram (figure 1) indicates some of the boundaries that teacher educators in any setting or context might face.

Activating your prior learning and knowledge: self-reflection prompt questions to nudge thinking about and contextualising boundaries:

- Exploring the range of boundaries that might exist (figure 1), can you identify particular boundaries that you face as a teacher educator? Are there others that you would add to figure 1?

- Focusing on two or three of the boundaries that you can identify, in what ways do these boundaries enable or constrain or shape your development and your practice as a teacher educator?

Navigating the boundaries – boundary crossing

Teacher educators in all settings have to navigate diverse and complex contexts. In many cases, teacher educators were themselves teachers prior to becoming a teacher educator whilst others may have been educational researchers. Therefore, in becoming a teacher educator their practice tends to rely on these experiences as a teacher in primary or secondary education and/ or the experiences in academia. Gradually developing teacher educators become more open to the complex and specific world of teacher educators. Being in a university, the teacher educator has to deal with a research culture which does not always comply with the need for practitioner research or the professional orientation in teacher education and the associated partnership activity that is often required for supporting teaching and learning within the teacher education programmes. Being in a school, the school-based teacher educator has to deal with a culture primarily focused on the learning of pupils in primary or secondary education rather than the learning of higher education students or the professional development of (beginning) teachers, and has to cooperate with teacher educators and teacher education in universities. These different contexts and settings bring the challenges of navigating the different boundaries as teacher educators.

Teacher educators fulfill multiple roles in education, research and service (Davey, 2013) and as teachers of teachers, researchers, mentors, curriculum developers, gatekeepers and brokers (Lunenberg et al. 2014). Being an accomplished professional in one of these roles does not mean that one is also versatile in the others. Additionally, in developing towards being an accomplished professional or expert, the teacher educator becomes connected to other networks and can eventually play a prominent role in these wider (professional, disciplinary, research, policy, societal) networks outside the institutional context. In all these examples teacher educators are crossing boundaries. Boundary crossing is strongly connected with learning. In an increasing specialized and fragmentized world connections between what is already part of myself and what is not (yet) part of me are important in becoming member of a wider community. In fact: all learning involves boundary crossing. As Akkerman and Bakker (2011: 132-133) state, “The challenge in education and work is to create possibilities for participation and collaboration across a diversity of sites, both within and across Institutions”. Boundary crossing may help to develop new connections, knowledge and skills, which may eventually lead to changes in professional self-conception and professional identity for those participating, and to new shared conceptions and practices.

What is boundary crossing?

The concept of boundary crossing came to the fore when management consultants and researchers became dissatisfied with linear vertical concepts of developing expertise. The main reason is that professionals work in multiple contexts and that development of expertise occurs often in situations where (teams of) professionals have to deal with (teams of) other professionals, within or across institutions, or with (groups of) lay people. In these situations everybody brings in their own expertise, but the kind of expertise to be developed is not pre-defined and solutions of problems are context-specific. As specialization and division of labour increases, these situations, where horizontal learning takes place, occur more often (Engeström et al., 1995). “Hence, working and learning are not only about becoming an expert in a particular bounded domain, but also about crossing boundaries” (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011, p. 134). Boundary crossing is, in contrast to conceptions of transfer, two-sided. It refers to ongoing, two-sided, interactions between contexts. It affects not only the knowledge, understanding and professional identity of participating individuals, but also the practices and development of participating institutions at large. Boundary crossing values diversity instead of considering it problematic. It may lead to new shared conceptions, understanding and even organizational entities. Boundary crossing is closely related with the cultural historical activity theory on expansive learning (Engeström, 1987), in which two ‘activity systems’ interact with each other to construct shared in between spaces of practices that provide potential for rich personal and professional learning. In teacher education, the interactions and communications between and across sectors and practitioners in various institutions and professional network contexts creates opportunities for learning, across and through the various boundaries.

Boundary crossing and third spaces

Boundary crossing may lead to the creation of ‘third spaces’ in which those participating in the dialogue between two or more contexts or ‘activity systems’ generate a community or organization to deal with the mechanisms of learning. In teacher education references to these third spaces are made e.g. in the cooperation and the collaborative learning of teacher educators in schools and teacher educators in universities. In the context of supporting initial teacher education, Zeichner (2010) suggests that new emerging ‘third spaces’ enable learning at the boundaries to create new hybrid ways of being which bring about a transformation of self or practice. More so, he suggests that we should be pursing the creation of these hybrid transformative third spaces to transform learning and practice, drawing from and recognising the individuality as well as the shared, new synergies of campus-based and practicum-based learning and practitioners. These third spaces are not just about crossing boundaries – but the creation of new spaces or new practices in which the professional practice is transformed.

In the Netherlands these third spaces are institutionalized in so-called ‘opleidingsscholen’ (professional development schools) formal learning spaces created to support the development of beginning teachers. In Scotland, there are no professional development schools as such, but the partnerships between universities and the local education authorities (who provide state funded school education) creates third spaces in a variety of different ways: for example the co-creation and support professional learning Aberdeen University’s ‘network days’ for distance learning students (neither school nor university led – but co-constructed by both) or Glasgow University’s ‘hub schools’ for taking a ‘clinical practice’ approach to supporting student teachers (Conroy, Hulme, & Menter, 2011).

Enabling boundary crossing

The review by Akkerman and Bakker (2011) found four mechanisms of learning at boundaries: (a) identification, (b) coordination, (c) reflection and (d) transformation. Identification occurs in a dialogue between participants of two contexts, they learn to understand each other’s differences and similarities and, with coordination, identifies effective means and procedures to cooperate efficiently in the distribution of work. Reflection is in place when participants make more explicit their assumptions about, and understanding of, their own context. Boundary crossing creates here the possibility to look at one self or one’s own context through the eyes of the other. Transformation refers to profound changes in practices, or the creation of a new, in between, practice (new hybrid roles). Transformation can be expected when confrontation occurs and participants are reconsidering their current practices and interrelations.

However, even when transformation takes place: “Dialogical engagement at the boundary does not mean a fusion of the interesting of the social worlds or a dissolving of the boundary. Hence, boundary crossing should not be seen as a process of moving from initial diversity and multiplicity to homogenity and unity but rather as a process of establishing continuity in a situation of sociocultural difference” (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011, p. 152).

As teacher educators the concepts of boundaries, boundary crossing and even boundary artefacts (objects which are commonly recognised in different settings but serve different purposes and can influence and shape practice, (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011) serve useful purposes in conceptualising the development and reshaping of ourselves and of our professional practice as we become teacher educators and support the professional learning of new and beginning teachers.

For wider discussion and consideration with peers:

- How do teacher educators navigate the transitions between boundaries?

- What is the impact of learning at the boundaries in relation to teacher educators?

- What support or evidence if there for practice development or change happening as a result of learning at the boundaries or boundary crossing?

Idea for online stimulus:

to set up one or two short professional conversations between different teacher educators – maybe even a focus group discussion – around the boundaries that they see are enabling and constraining their professional practice, professional learning and professional role. Perhaps take this from one or two different country contexts?

References

Akkerman, S. & Bakker, A. (2011). Boundary Crossing and Boundary Objects. Review of Educational Research 81(2), 1-5.

Conroy, J., Hulme, M., & Menter, I. (2013). Developing a ‘clinical’ model for teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 39(5), 557-573. DOI: 10.1080/02607476.2013.836339

Davey, R. (2013). The Professional Identity of Teacher Educators. Career on the cusp? Abingdon: Routledge.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding – an activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki: Orienta-konsultit

Engeström, Y., Engeström, R., & Kärkkäinen, M. (1995). Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: Learning and problem solving in complex work activities. Learning and Instruction 5(1995), 319-336.

Lunenberg, M., Dengerink, J. & Korthagen, F. (2014). The Professional Teacher Educator. Roles, Behaviour, and Professional Development of Teacher Educators. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers

Zeichner, K. (2010). Rethinking the Connections Between Campus Courses and Field Experiences in College- and University-Based Teacher Education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1-2), 89-99.

Key words Boundaries; boundary-crossing; teacher educator; expansive learning

[tabby title=”Further Reading”]

Boundaries and boundary-crossing (PDF)

[tabby title=”Blog Posts”]

[wp-rss-aggregator source=”2957″]

[tabbyending]