Interrogating Professionalism

Views on teacher education

September 11, 2018

Explicating students’ beliefs about good history teaching

October 20, 2018Interrogating Professionalism

Teacher educators frequently invoke the concept of ‘professionalism’ in their work with students. It is usually presented as an unqualified good, a set of values that aspiring teachers should aim to achieve. In some countries (e.g. Scotland), suites of ‘professional’ standards appropriate to different career stages have been developed, as well as a code of ‘professional’ conduct (see GTCS, 2018). It is questionable how many classroom teachers could recall what exactly these specify: the bureaucratic documentation can seem remote from daily practice. There is also a universal exhortation to engage in ongoing ‘professional learning’ through a variety of activities – e.g. collaborative projects, classroom research, advanced qualifications.

The intentions behind most of this are benign, though there is also an element of territorial expansion by ‘professional’ organisations. But any concept that is employed so frequently and uncritically deserves to be interrogated. A study of the way in which professions have developed historically shows that, while the original motivation was to exclude charlatans and provide better service, over time they have tended to become protectionist and self-serving. In the case of lawyers and doctors, for example, their use of a rhetoric of public service rests uneasily with their poor record of transparency when faced with complaints or evidence of malpractice. The processes of so-called ‘regulatory’ bodies often seem biased in favour of the ‘professionals’ and stacked against members of the public.

In the case of teaching, it needs to be asked whether the concept of ‘professionalism’ may be as much to do with promoting occupational conformity, and ensuring a continuing role for existing institutions, as with encouraging the kind of critical thinking and creative practice that officials claim they want to promote.

In the case of teaching, it needs to be asked whether the concept of ‘professionalism’ may be as much to do with promoting occupational conformity, and ensuring a continuing role for existing institutions, as with encouraging the kind of critical thinking and creative practice that officials claim they want to promote.

Shallow ‘groupthink’, in which the language of policy documents is recycled unquestioningly, is unlikely to produce a workforce prepared for the challenges that lie ahead. Teacher educators need to reflect carefully on their use of a form of discourse that, arguably, is in danger of becoming discredited.

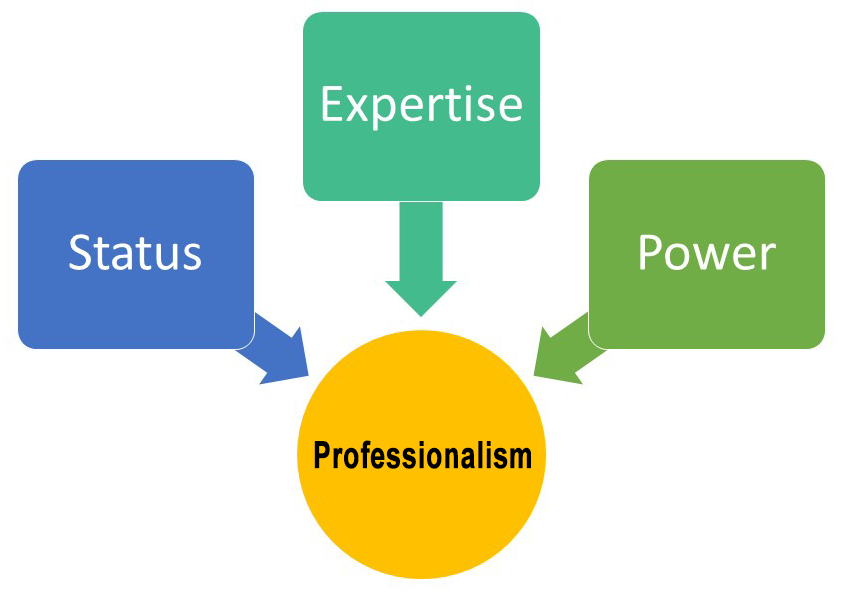

There is, of course, already a substantial literature on teacher professionalism but much of it is inward-looking, concerned with the changing nature of professional expertise and perceived (political) threats to status. What is lacking is an informed awareness of historical evolution (but see Hargreaves, 2000) and a critical understanding of the way in which claims of professionalism are linked to questions of discourse, power and social class. An updated sociological perspective, of the kind offered by Macdonald (1995), would open up territory that is largely ignored in the prevailing upbeat account of professional principles and practices.

As a starting point, teacher educators might find it instructive to ask themselves (and their students) the following questions every time they encounter the word ‘professional’ or one of its derivatives:

- What exactly is signified by the term?

- Would another word serve equally well?

- What is the evidence-base for the appeal to professionalism?

- Whose interests are served by the invocation of the concept?

- What does the usage reveal about power, status and expertise?

- Is there scope for an alternative account?

By addressing these questions, we are less likely to continue repeating tired rhetoric and may manage to come up with a stronger and more persuasive justification for the work that we do.

References

General Teaching Council for Scotland (2018) ‘Professional Standards’ and ‘Code of Professionalism and Conduct’. Available online at The General Teaching Council for Scotland

Hargreaves, A. (2000) Four Ages of Professionalism and Professional Learning, Teachers and Teaching, 6 (2): 151-182.

Macdonald, K. M. (1995) The Sociology of the Professions. Sage: London.