New ways of governance: can teacher educators take responsibility?

How research on reflection has changed my view on reflective practice

March 23, 2019

“Traditional” Teachers: Current Teaching Methods and Nurturing Independent Learners

April 7, 2019New ways of governance: can teacher educators take responsibility?

One aspect of social change is how conceptions about good government and governance change. It is reported that teacher educators and teacher education in general experience that government policy is constraining their pedagogical space for professional discourse , diversity and curriculum development by rolling national agendas of standardisation and centralisation and by their focus on standardized test scores (Swennen & Volman, 2016; Zeichner, 2016). MacFarlane (2005) concluded that these developments also lead to civic disengagement among academics. Do teacher educators have to accept this situation as a matter of fact, or can they overcome these constraints?

Types of educational governance

In November 2018, the OECD published two reports on governance. One (OECD 2018a) is dealing with the question: How decentralised are education systems, and what does this mean for schools? According to this report schools in The Netherlands, England, Belgium(Flanders), and Scotland have a relative high autonomy in decision making, and schools in France, Spain and Norway a relative low autonomy. Finland is the only country where decision making takes place on multiple levels.

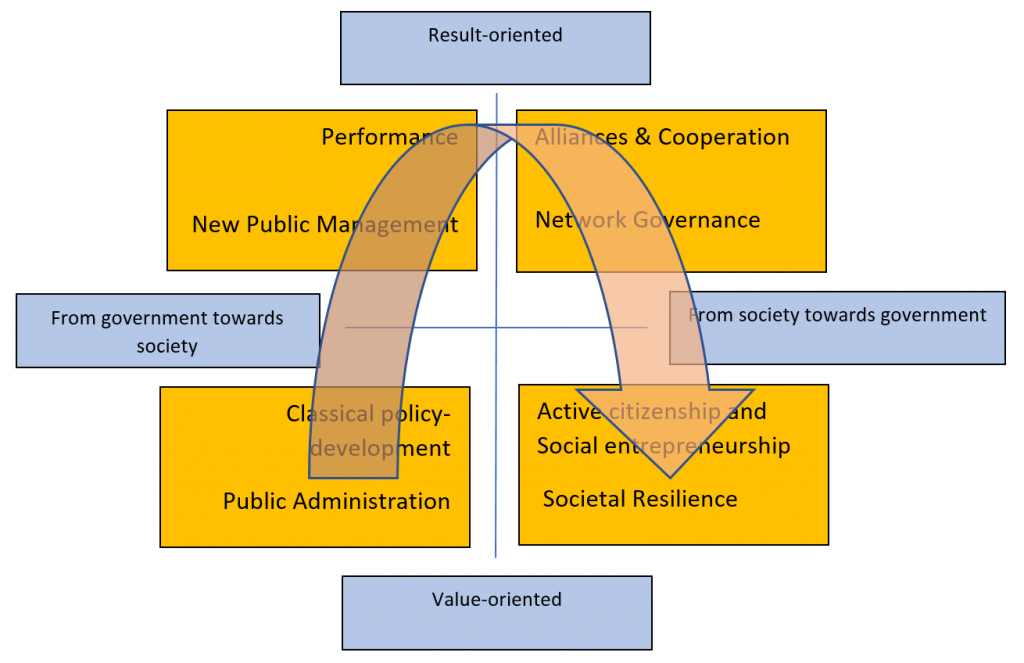

In the other OECD report, written by Frankowski et al. (2018), which mainly deals with the Netherlands, four types of governance are discerned, along the axes result oriented vs value oriented and inside-out vs outside-in (from the government perspective).

How to overcome the trap of increasing government control?

Having a closer look at this model, the interesting phenomenon is that it shows a development that started in the last century, labeled by Waslander et al. (2017) as a development ‘from government to governance’. This new type of governance was highly output-oriented, with standards, competency-lists, and in most countries with the government as main and initial actor. At the end of the century it developed towards a New Professionalism (Hargreaves, 2000), a type in which the teachers were empowered to contribute to government policy, but found themselves at the end bound to complex sets of regulations regarding curricula and competencies. Already in 2000 Hargreaves stated that teacher professionalism and professional learning were in this situation on the crossroads: ”becoming more extended and collegial in some ways, more exploitative and overextended in others. The puzzle and the challenge for educators and policymakers is how to build strong professional communities in teaching that are authentic, well supported, and include fundamental purposes, and benefit teachers and students alike (collegial professionalism), without using collaboration as a device to overload teachers, or to steer unpalatable policies through them.” (p. 166).

And still we see a political atmosphere in which parliaments on the base of incidents call for strong measures of governments, and that consequently teachers, educators, schools and teacher education are confronted by these governments with an ever increasing load of quality assurance systems and accountability.

Professionals in the lead

To change this situation, professionals themselves should be more in the lead, not isolated, but together with other parties and individuals. Social (digital) networks make this possible. Ultimately, it is about cultivating trust that professionals are striving for the common good, and are willing to engage with everyone. This implies another vision on accountability and responsibility. It means that professionals inquire their intentions, behaviour and results, not on the base of checklists from above, but with the responsibility lying as close as possible to the ownership of practitioners. Governance will take on a different meaning, is more value-oriented and development-oriented, takes into account complexity and is more tailored to what is needed in specific situations. It is another form of autonomy, not focused on striving for independence, but on developing strong relationships, in and outside the own professional group.

Does this mean that we can throw away professional standards? No, of course not, but the standards get a different character: they are the result of dialogue, especially among the professionals themselves: teachers, teacher educators and researchers, in consultation with the target groups for who they work. They are not cast in concrete, but serve more as a frame of reference to which the individual professional can relate, and are regularly adapted to new shared insights.

The pivotal role of teacher educators

University-based teacher educators have a role as a ‘broker’ (Lunenberg, Dengerink & Korthagen, 2014). They are expected to have extensive professional networks, not only with teachers and school leaders, but also with researchers, publishers, policy-makers etc. As mentor and coach they are expected to know how to deal with diversity and different perspectives. This way we might move to the point where the dichitomy between state rule and decentralised rule can be overcome. This implies more attention for value-oriented education and for active citizenship. In this way teacher educators can play a pivotal role and become ‘social entrepreneurs’ in ICT-supported professional communities and in the cooperation with multiple stakeholders, bridging educational practice, research and policy, and thus contribute to the quality of educational governance.

References

Frankowski, A. et al. (2018), “Dilemmas of central governance and distributed autonomy in education”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 189, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Four Ages of Professionalism and Professional Learning. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 6(2), 151-182.

Lunenberg, M., Dengerink, J. & Korthagen, F. (2014). The Professional Teacher Educator. Roles, Behaviour, and Professional Development of Teacher Educators. Rotterdam/Boston/Taipei: Sense Publishers

Macfarlane, B. (2005). The Disengaged Academic: the Retreat from Citizenship. Higher Education Quarterly, 59(4), 296–312.

OECD (2018). How decentralised are education systems, and what does it mean for schools? Education Indicators in Focus #64. Paris: OECD

Swennen, A. & Volman, M. (2016). Teacher educators’ struggles for monopoly and autonomy over teacher education in the Netherlands, 1990-2010. In: T.A. Trippestad, A. Swennen, & T. Werler (Eds.). The Struggle for Teacher Education: International Perspectives on Governance and Reforms. Bloomsbury Academic.

Waslander, S. & Pater, C.J. (2017). Sturingsdynamiek in het voortgezet onderwijs. Tilburg: TIAS School for Business and Society, Tilburg University.

Zeichner, K. (2016). Independent Teacher Education Programs. Apocryphal Claims, Illusory Evidence. Boulder, Colorado: National Education Policy Center, School of Education, University of Colorado. 29 pp.